Shells do not choose where to fall. Wars of front-line villages in the Donetsk oblast

"God, I do not even know, — Anna Dombay, the chairman of the front-line village of Chermalyk, breathes out when I ask her about the prospects of this territory. — I think if the hostilities stopped, it would be possible to rearrange everything bit by bit within five years".

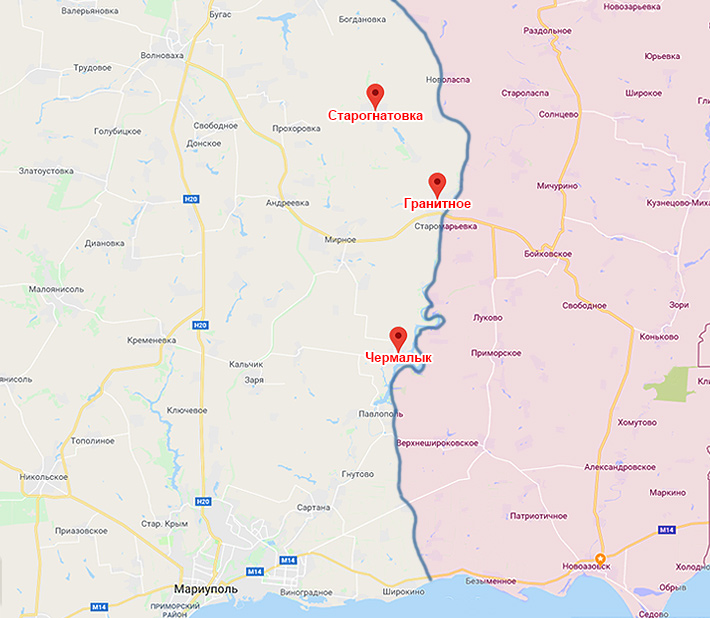

The settlements at the edge of front have been stuck in some kind of limb for several years. The line of demarcation in some places is still slowly shifting, but Chermalyk is protected from radical changes by the serpentine bends of the wide Kalmius — a river which also peacefully flows in the center of Donetsk, the "capital" of one of the puppet "republics".

Outskirts of Chermalyk. The river is a line of demarcation

The former district center of Telmanove is on the other side of Kalmius, but since 2014, Chermalyk and a number of right-bank villages with a predominantly Greek population have been transferred under the authority of Volnovakha. Many of these villages no longer fall into the epicenter of a low-grade war, but the continuing state of uncertainty prevents them from recovering from recent disturbances. The life in a constant tension makes impact on the condition of local residents. Anna Dombay says that there are 68 oncology people in Chermalyk today, in the village where about half a thousand yards are being inhabited.

"I was born and grew up in this village, I work for 18 years in the village council, — the village council secretary Natalia Arikh says. — It used to be a rare case among senior citizens when a person came undone, one grandmother for ten years. Do you know their number now? Horror. Whole families. We buried two teachers for a month. At first, he became insane, and then she…"

In the morning before our arrival, Chermalyk and neighboring villages listened to the cannonade again. At the time, we just left for this region from a quiet and absolutely safe regional center, Kramatorsk. From three to four in the morning, hardly fit for driving broken road, snow-white KIA RIA of Yuriy Lytvynov, the employee of the NGO Country of Free People, gathered other activists through the city to help the villagers with humanitarian aid and return home by the beginning of the next day.

Stop 1: Starohnativka

Konstantin Merenik, the owner of a store in the village of Starohnativka, says that the roads were so far, so good while the tanks were driving along them, "smoothing" the ground with the remains of long ago vanished asphalt. The roads in Starohnativka and around it have hardly seen at least one major repair in the last quarter of a century.

Before the war, Merenik had a store on the outskirts of the village, but when Starohnativka was being fired, he rented a room in the center. To do business at that time and in that place was akin to a feat: the nearest large settlement, Mariupol, where the local people used to carry goods from, was itself on the verge of a fall, and the shelves and stores of wholesalers and supermarkets were as empty as the stores of the villages like Starohnativka. The obstructions apart from pits appeared on the habitual roads — checkpoints.

With the cessation of active fighting near Starohnativka, another war, the civil one, came to the village: for humanitarian aid. Suspicion, envy and hatred of those who allegedly receive more divided neighbors, friends and even relatives.

The tension is felt in Starohnativka immediately. When I and Varia, the deputy of the local council and one of the recipients of the new "humanitarian aid", are walking along the center of the village, a few indignant young women stop her with, apparently, beforehand prepared questions: who is being given help to, why they are not given help and on what grounds Varia receives the "humanitarian aid" herself.

It happens that humanitarian organizations bring aid to all rural yards — for example, briquettes for heating. But more often, the supplied "humanitarian aid" is designed for people of certain categories: those who are over 65 years old, disabled, low-income, as well as large families. And this approach proves its harmfulness today.

The content of the lists of recipients in the villages is usually known in advance, as well as criteria upon which they are being selected. But this does not stop the ugly scenes that we observed then in each of the visited settlements. Varia says that one of the trouble makers brings up two children together with their father, but is not officially married in order to have the status of a single mother — a usual story for places where unmarried women with children have the right to some kind of humanitarian assistance or any benefits.

The employees of Country of Free People in these villages have a twin challenge. Firstly, they need to collect the signatures of local entrepreneurs under the documents: Country of Free People is ending a project, according to which the most vulnerable, as it is thought to be, villagers received a kind of "electronic certificate" for almost $60, for which they could buy products in shops-partners of the project. The store of Konstantin Merenik is just one of them.

Secondly, they escort the UN trucks which, within the framework of one of the organization's programs, distribute just hatched in the incubator domestic chicks in the front-line settlements. A few dozen recipients in each of the villages can get either twenty ducks or turkeys, or thirty chickens.

Meanwhile, we are just going to Starahnativka — the first stop on our route — Oleksandr Petrov from Country of Free People praises the system invented by the UN staff: each recipient of the chicks, signing for him-/herself in the list prepared by the local administration, takes the business card of the organization's member which then exchanges for the intended for him batch of birds. This, as it were, prevents the possible confusion and speeds up the distribution process.

However, the tenuous system does not go under the test by a clumsy reality. In an absolute chaos, when the members of the humanitarian mission are tirelessly attacked by the recipients and dissatisfied, and the line of the first is unexpectedly wedged in by the delegation from a neighboring village, which was not expected at that moment, a peasant who was left without chick appeared: one batch was in some way stolen. Sasha and Yura, who were harnessing the people's power under a boiling sun for an hour and a half before the detection of this loss, are upset. Having stayed in the village to find a reserve among the remaining chicks, they find the offended man in order to give it to him.

Hranitne: continuation of war

At the next distribution point, in the village of Hranitne, everything happens much faster. A well-organized government is felt immediately: the queueing and distribution takes no more than half an hour, so I barely have time to talk to Yevhenia Herehiyiva, the owner of a store in Hranitne, which also participated in the Country of Free People program.

Before the war, Yevhenia and her husband had three stores — two remained on a territory beyond Kyiv's control, where the Herehiyivy no longer have access. There, as well as in Hranitne, this family is in black book, the entrepreneur says: in 2014-15, there were only three or four of all such families in the whole village who openly supported Ukraine and helped the Ukrainian military. Yevhenia remembers that at that time, their store was repeatedly threatened to burn. In addition, the local residents set up a boycott to the Herehiyivy, having temporarily stopped to buy from them.

Like Konstantin Merenik, Yevhenia Herehiyiva says that the humanitarian aid, which is given only to people of certain categories, destroys the village. Hranitne differs greatly from Starohnativka: it still shows today that it was rich recently. However, the granite quarry, which gave the work to the majority of local residents, gradually winded the work down to be finally closed after the outbreak of hostilities.

Traces of war in Hranitne

Today, there is almost no place to work, but many are not interested in legal employment, having got used to live at the expense of humanitarian aid. The remaining youth in Starohnativka can have additional income just from growing and selling cannabis — an old local business. Herehiyiva says that when she and her husband opened a cafe in Hranitne after the beginning of war, they could not hire someone from the local to work for a long time. Having a confirmed income of more than $65 per person means a forfeiture of the right to receive the notorious "humanitarian aid".

When I told Yevhenia goobye, several villagers from those who have received nothing stay near the UN car next to the village council. A middle-aged thin man in a sports suit somewhat perplexedly asks Sasha about the criteria for selecting the recipients, and then asks for a brochure about the poultry care from those that were given along with the chicks:

"I will take care of my own ones", — and calmly leaves.

Three women stay near the village council. The mother of a schoolgirl who says that she is raising a child alone and does not receive any help, for some reason holds a list of those who were given chicks (according to her, rich businessmen). From her remarks, it becomes clear that some of the residents of Hranitne have a conflict with the local administration, precisely because of the unfair, as they say, distribution of humanitarian aid. They even sent a collective letter of complaint to the Verkhovna Rada demanding to displace the head and secretary of the village council.

The comments of other women, who joined the conversation, give the impression that there is a group of permanently offended local residents, keeping a record of every aid and almost all of its distributors and beneficiaries. One of the women is seriously offended at the secretary of the council because she refused to issue an "IDP certificate" to her relative, who actually lives not in Hranitne, but in one of the occupied cities.

"It can change at any moment, what will happen when those come here..., — she whispered confidently, nodding to the occupied territory. "Do they think about what will happen to them? They have offended so many people here".

I ask: "So, do you think that they will come to protect you from there?"

The woman does not immediately understand the question and continues to think aloud about "people's revenge". But then three women laugh unhappily: "Both those and these are not thinking about people, they are all the same!"

Chermalyk. "There is no justice!"

"I will not do anything else, it's useless. They want to get some benefit from each fund".

Anna Dombay, the head of Chermalyk, a strong-willed woman, utters these words almost plaintively. In Chermalyk, the same pattern as in Hranitne is observed.

She says that the criteria by which humanitarian organizations identify people in need of assistance are unfair. But the most unpleasant thing is that a number of quite primitive fraudulent schemes are based on these criteria. Spouses divorce to receive help for fake single mothers. Someone hides their real incomes. Many people simply do not work.

"People have forgotten how to work, — the head of the village says. — Nobody wants to even mow the grass for money. No one wants to work - everyone is waiting to either get some assistance or steal metal".

Like Hranitne, Chermalyk flourished until recently. Since the early 1990s, there was the richest agro-farm of the Mariupol Metallurgical Plant named after Ilyich. However, in 2011, the plant got a new owner — Metinvest of Rinat Akhmetov. His companies were also interested in agriculture, but in a different way. Farms were ruined in a few years. The war and the local unemployed youth ended what was left of them. The state farm of the Chermalyk villagers, which, after the collapse of the USSR, was not decommissioned, went to the use of Akhmetov's HarvEast Holding. So the war and the new owner left the inhabitants of Chermalyk with nothing.

The internal struggle for humanitarian assistance undermines the very foundations of the local community. The leaders of Chermalyk, like their counterparts in other front-line villages, seriously say that the distribution of the aid in such a way should be stopped. We should not divide people — shells do not choose where to fall.

In Chermalyk, realizing that the same people constantly receive help (and not necessarily the most needy ones), they tried to find a solution. If the aid comes not for the whole village, it is distributed to those who have not receive anything before. Donors, fortunately, began to delve into the nuances and do not oppose such a solution. Thus, at the time of our arrival, there were only about twenty households, which did not receive anything. But this did not save the local administration from the scandal. While they were distributing chicks in the yard of the village council, some dissatisfied people line up in front of the secretary's office.

An elderly woman says she specifically came to the village council to observe who will be the recipient of the UN humanitarian aid. She remembers who had gotten it before. Natalia Arikh also remembers almost thoroughly, who and when got the aid.

"...Are my living conditions better than hers or do I have larger pension?", — complains the visitor.

"She has three families in the house, do you understand this?", — the secretary objects.

"Well, that's their problem!... I do not want these chickens! It's just painful that they make me seem "rich"! I get $65 and spend everything on medicine!"

The argument drags on, and it becomes obvious that simple arguments do not work.

"Correct me if I'm wrong, — Arikh says to me at some point. — At the end of July that woman received 20 turkeys and $21 to buy food for them, and then 10 kilograms of fodder. She was selected to receive assistance from the Red Cross — $85 cash, 450 kilograms of fodder and ten light bulbs worth $38. Then, in January, she was selected to receive $32 per month in the course of six months. In addition, in 2017, Rinat Akhmetov's Foundation gave her humanitarian aid... "

"Why do not you talk about those who received $1000, $600, $400?", — the visitor starts screaming.

Someone calls Natalia Arikh and she leaves. The old woman is waiting for some time to continue, getting some kind of sadistic pleasure from this dispute.

"Let them stop their aid, and it will be even better, because there is no justice!", — she concludes, reluctantly leaving the office.

"Have you been in my shoes?", —Natalia Arikh asks without a smile, when we meet again in the corridor of the village council. Anna Dombay looks very tired in the yard. Both of them seem to want us to leave as quickly as possible and to get over this hard day.

Orlivske. No matter how hard you try, you still cannot please everyone

We are happy to move on. Orlivske is a small village within the Chermalyk village council, but located a good distance from it. It's evening already, we all want to return to Kramatorsk at least by night. Until now, none of us have eaten, and I'm surprised that my companions still have energy for distribution of chicks, joking with their comrades and explaining something to every rural brawler. This is their usual working day.

There are less than 200 residents in Orlivske. This is one of the poorest and abandoned villages in the area. Instead of handing out 20-30 chicks to certain households, members of the local Protestant community, decide to distribute ten chickens to each household.

To the wall of the hut, which activists have restored and use as an office, club and house of prayer, lists of humanitarian aid for each household are attached. Visually, the sheets do not differ a lot from each other. That is, the activists did everything possible to divide the incoming aid equally, hoping to minimize the likelihood of conflicts and misunderstandings.

Center of life of the Orlivske community

But there are dissatisfied people even here.

The residents of the village are gradually gathering near the building of the club-church. Somewhere aside, two women demand to show them already irrelevant lists of selected aid recipients. The women are being explained that according to the criteria, developed by the humanitarian organization, they do not have the right to receive this assistance.

Women know about this, but they are indignant when they see a 90-year old man in the lists, they say he does not need these chicks. They are also outraged by the fact that local activists decided to distribute chickens not according to lists, but for everyone.

"It's to take everything for themselves!" , — they suddenly declare.

When we leave the activists to distribute the chickens on their own, women hastily wedge into the disorderly queue to get them.

Yulia Abibok, OstroV